[ad_1]

For five long weeks, the White House hung in the balance as one of the closest, most wrenching presidential campaigns in history went deep into overtime.

It all came down to Florida, where Republican George W. Bush was finally declared the winner, by Supreme Court decree. The official margin was 537 votes.

But in 2000, one state was even closer.

Lost amid Florida’s tumult and all the legal gladiating was Al Gore’s victory here in New Mexico, where the Democrat prevailed by a mere 366 votes.

The outcome may have lacked urgency; Florida’s 25 electoral votes decided the contest. But the result established New Mexico as one of the country’s foremost presidential battlegrounds, a status reaffirmed in Bush’s 2004 reelection campaign when he won the state by less than a percentage point.

Since then, it’s been one Democratic victory after another — none of them close.

For much of its history, the West was Republican ground. Today, it’s a bastion of Democratic support, a shift that has transformed presidential politics nationwide. Mark Z. Barabak explores the forces that remade the political map in a series of columns called “The New West.”

“We’re not purple,” said Joe Monahan, a blogger who has chronicled New Mexico politics for decades. “We’re blue. Very blue.”

The change is part of a pattern that has remade the West, turning the onetime Republican redoubt into a deep well of Democratic support. In this series, called “The New West,” I’m exploring how that change, from the Pacific coast to the Rocky Mountains, came about, resetting the political competition nationwide.

To a large extent, it’s a story of movement.

People relocating from more liberal climes, like California.

Newcomers filling up cities and suburbs, as rural areas recede.

Latino influence expanding.

And, not least, Republicans shifting dramatically rightward — especially on issues such as immigration and abortion — antagonizing that burgeoning Latino population and butting up against wary Westerners bridling at those telling them how they should live their lives.

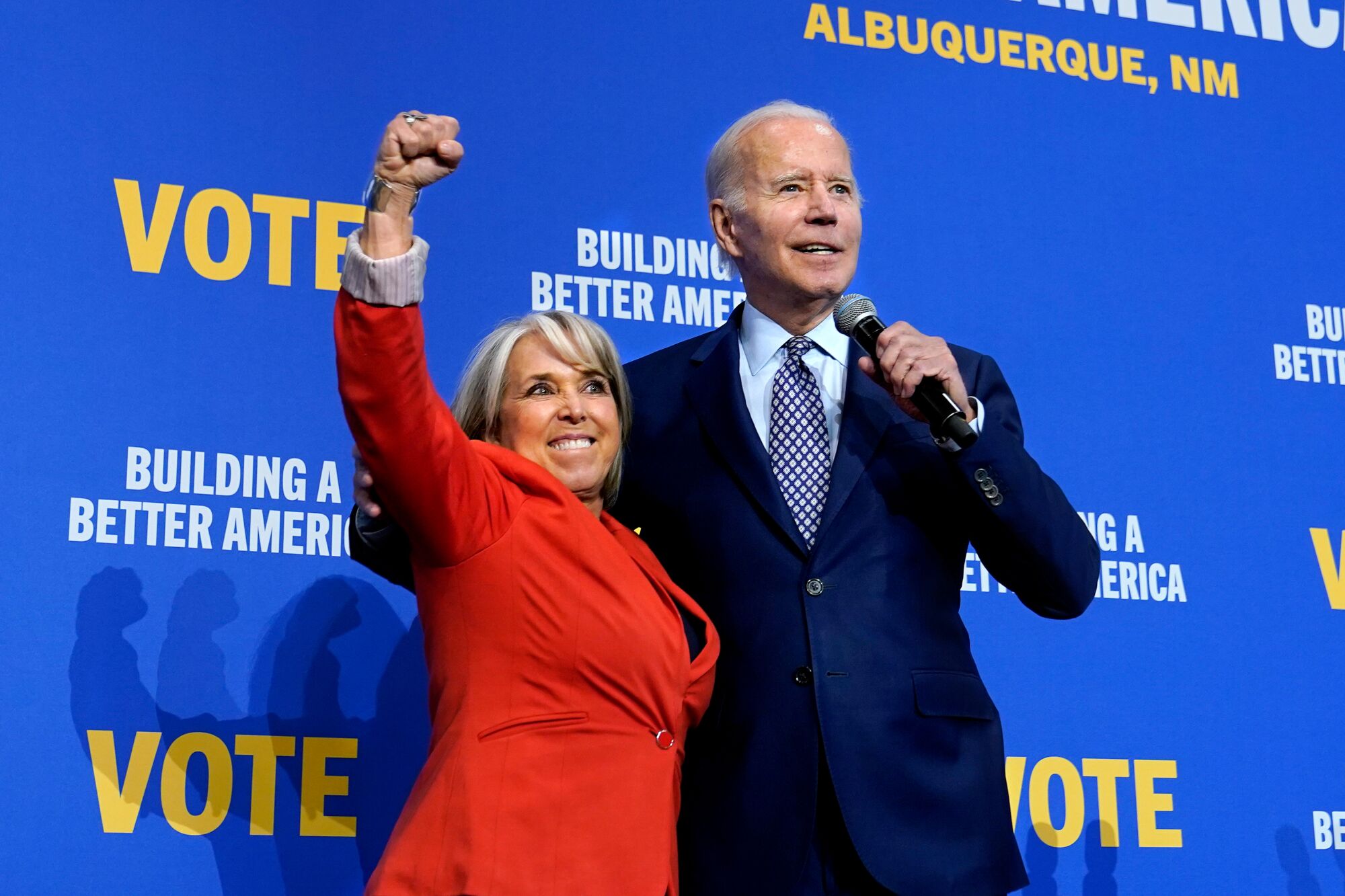

President Biden and New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham acknowledge the crowd at an Albuquerque rally in support of Grisham’s 2022 reelection.

(Patrick Semansky / Associated press)

“They don’t like government interference,” said New Mexico’s Democratic governor, Michelle Lujan Grisham. “What I mean by that is: Don’t make healthcare decisions for me. Don’t talk to me about what you deem to be equality. Don’t tell me what books I can or cannot read. Don’t tell me who I can marry.”

In sum, she said, “Don’t tell me what to do.”

::

After more than a decade in Los Angeles, Tarra Day was ready for a change.

The Hollywood makeup artist decided to return home to New Mexico, where she grew up and her father still lived. It was, she said, “a leap of faith.”

Things couldn’t have gone better.

It was 2005 and Gov. Bill Richardson was working to diversify New Mexico’s tepid economy through tax rebates and other incentives aimed at making the state a hub of movie and TV production. The industry boomed. Day found plenty of work and bought a ranch-style home amid the cottonwoods and adobes of Santa Fe, the history-rich state capital.

Former New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson, left, worked to diversify the state’s economy by courting Hollywood and entrepreneurs such as Sir Richard Branson, whose spaceflight company operates north of Las Cruces.

(Jeff Geissler / Associated Press)

A Republican who became a Democrat when Bill Clinton was president, Day, 61, is part of New Mexico’s two-decade political transformation. (“I wanted a party that would be open to gay rights, women’s rights,” she said of her switch from the GOP.)

The state hasn’t exactly boomed over the last 20 years. New Mexico’s population, about 2.1 million residents, is not a whole lot more than it was in 2000. With the exception of the thriving southeast oil patch called “Little Texas,” most of the meager growth has been in and around its largest cities.

That’s boosted the strength and influence of Democratic-leaning Albuquerque, Las Cruces and Santa Fe at the expense of New Mexico’s rural areas, which tend to vote Republican.

The entrance to Netflix’s ABQ Studios in Albuquerque. New Mexico has become a hub of TV and film production, drawing an influx of newcomers, including many who relocated from California.

(Susan Montoya Bryan / Associated )

The same political and demographic shift has happened throughout the region.

There is a mythology of the West, a romantic notion of wide-open spaces and rugged individuals spread far beneath the big, open sky.

Although those people and places certainly exist, as anyone who’s driven the empty high-desert expanse between Albuquerque and Santa Fe can attest, most Westerners live in cities. In fact, a greater percentage of residents are urban dwellers — 90%— than anywhere in the country.

Most of them favor Democrats, like Stacy Skinner, 58, another Hollywood migrant, who does hairstyling as well as celebrity makeup. Two months ago, she leased an apartment near Albuquerque’s hulking Sandia Mountains, importing her political views from California along with her.

Though Skinner has concerns about crime and whether the Democratic Party has gone soft on the issue, she fully intends to support President Biden’s reelection, having backed every Democrat seeking the White House since Barack Obama.

“Republicans,” Skinner said, “have become the party of crazy.”

The country’s urban-rural divide dates back more than 150 years, to the Industrial Revolution, with people in cities historically more inclined to vote Democratic.

The chicken-egg question is whether those choosing to live amid the close quarters and disparate population of a city are, by nature, more likely to vote that way or whether living in a city makes an individual become Democratic over time.

New Mexico’s Roundhouse is the country’s only circular Capitol.

(Cedar Attanasio / Associated Press)

No matter.

David Damore, a political scientist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, suggested Republicans haven’t done themselves much good attacking cities, opposing diversity and adopting “a very old-timey message” intimating things were better when the West had fewer people, most of them were white and the economy was ruled by ranching and industries such as mining and logging.

Essentially the GOP “has become a party that’s anti-urban,” said Damore, co-author of the book “Blue Metros, Red States,” even as New Mexico and the West are becoming increasingly urban.

::

Sometime in the mid-1990s, New Mexico passed an invisible line and became a majority-minority state.

A substantial Latino population — or Hispanic, as many here prefer — has been deeply woven in the state’s culture and politics for centuries. Some families trace their lineage to the 16th century conquistadors.

As a result, there isn’t nearly the same degree of animosity toward Mexico and immigrants that fires much of the Republican Party and its political base.

“There is just a natural inclination in the state, first and foremost, to view things through a multicultural lens,” said Dan Sena, a Democratic strategist and New Mexico native who started his political career knocking on doors in Albuquerque.

But it’s not just the bellicosity of build-a-wall Republicans that puts off many New Mexico voters. It’s also the GOP’s messengers.

Charlie Gonzales of Taos joined other Democrats at the party’s 2008 national convention in Denver.

(Jack Dempsey / Associated Press)

As the Hispanic population expands — the proportion increases about 2% every five years, according to the state’s leading pollster and demographer, Brian Sanderoff — Hispanic clout has grown along with it. Today, New Mexico has more elected Hispanic officials than any state, most of them Democrats.

That’s made the party’s candidates more relatable and appealing to voters who see themselves reflected in the faces of the men and, increasingly, women wielding political power on city councils, at the Roundhouse — as the state’s circular Capitol is known — and in Washington.

“You’ve got every culture here,” said Carmenita Anaya, 62, a retired Albuquerque hospital administrator who experiences that blending of beliefs under her own roof. (She’s a Democrat. Her husband is a Republican.)

“It’s good to have people in there who know what New Mexico’s all about,” she said.

Republicans, meantime, continue “to advance these individuals that don’t necessarily represent the makeup of New Mexico,” said Dan Foley, who served 10 years in the Legislature, including two as a GOP leader. “When our candidates continue to be 60-year-old millionaire Anglos, which make up less than 1/10th of 1% of New Mexico, who wants to listen to you?”

New Mexico is one of the poorest states in the country.

Depending on the survey it’s either first or second, behind West Virginia, in its reliance on federal spending. For every tax dollar sent to Washington in 2022, $3.69 came back to New Mexico, according to the personal finance website MoneyGeek.

But unlike West Virginia, where even Democrats such as Joe Manchin make their livelihood attacking Washington, there’s not much benefit in New Mexico biting a hand that shovels billions each year into Medicaid, food stamps and three major national security labs, which employ tens of thousands of well-paid workers.

The Los Alamos National Laboratory is one of New Mexico’s major employers and a recipient of billions in annual federal funding.

(Albuquerque Journal via Associated Press)

It’s another way the GOP has grown out of step with New Mexico and its political sensibilities.

Even the state’s former Republican senator, the late Pete Domenici, took pride in the abundance he wrung from the federal Treasury — it’s a reason he was reelected time and again and revered as “St. Pete” when he left office in 2009.

“He’s one of the few Republicans I ever voted for,” said Paul Senna, 76, a former state budget analyst and lifelong Democrat, whose family roots reach back to the days of Spanish rule. “He did a lot of good things for New Mexico.”

Today, the five-member congressional delegation is entirely Democratic. The party holds all seven statewide offices and controls the Supreme Court and both houses of the Legislature by significant margins.

Biden is a strong favorite to carry New Mexico in 2024 after beating President Trump by 10 percentage points in 2020.

Once a bellwether, the state no longer swings with the national mood. It’s become Democratic bedrock, part of a politically crucial base in the reconstituted West.