[ad_1]

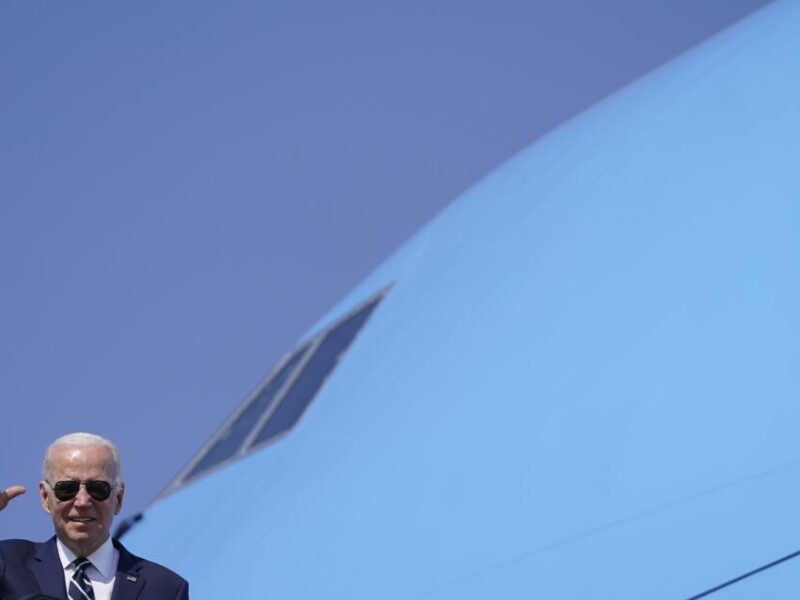

When President Biden visits Vietnam after his stop at the Group of 20 summit in New Delhi this month, he is expected to upgrade our two nations’ bilateral relationship to a “strategic partnership.” The shift will mark a significant turning for both countries. But it should not come at the cost of skipping the summit of the Assn. of Southeast Asian Nations around the same time in Indonesia. Biden’s choice to go to Hanoi — and send Vice President Kamala Harris in his place to Jakarta — is exactly backward.

The administration may claim otherwise, but in prioritizing the Vietnam visit, it is doubling down on its efforts to build a nation-by-nation Cold War-style security bloc to counter China and avoiding working with regional groups — such as ASEAN — likely to decide the Indo-Pacific region’s future. In an increasingly multipolar world, Washington needs to become more effective at navigating fluid and flexible coalitions, not rerun an old playbook.

The Biden administration insists its approach “is not about forcing countries to choose” between Washington and Beijing, but as we learned through interviews with former senior government officials and security experts in Southeast Asia, its actions often do not match its rhetoric. And the ASEAN countries — Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam — are noticing.

According to our interviews, Washington has publicly and privately pressured ASEAN members to turn down China’s global infrastructure projects, known as the Belt and Road Initiative, reduce their economic and technological dependence on Beijing and cancel their military partnerships with the People’s Liberation Army. What the administration heralds as “putting really big, important strategic points on the board” — for example, gaining additional access to the Philippines’ military bases and holding the largest-ever military exercise with Indonesia — many in the region view as thinly disguised attempts to form a new U.S. security bloc. Upgrading the relationship with Vietnam is just the latest example.

Worse, U.S. efforts to build its network of security partnerships are harming, not improving, ASEAN security concerns. For example, a trilateral initiative (known as AUKUS), in which the U.S. and the United Kingdom plan to equip Australia with nuclear-powered submarines, alarms some ASEAN states because it puts them geographically in the center of a dangerous U.S.-China tug of war.

Washington’s limited approach to ASEAN as a collective has done little to allay those fears. Biden’s hesitance is partly understandable. ASEAN can be vexingly slow and bureaucratic, but that does not make it any less central to the region. And unlike Beijing, Washington is on the outside of many of the organization’s economic and political collaborations — for example, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership that unites ASEAN, China, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea and Japan. Whatever points Washington is putting on the board in the region, they are not the ones that count most among nations focused on consensus-based multilateralism.

In the end, Washington’s drive for exclusive partnerships could leave it isolated. No amount of U.S. effort will consolidate ASEAN members as an anti-China bloc because these countries depend on China economically and politically. That long-standing position is unlikely to change, a former Singaporean defense official told us. And were these countries to turn away from China, they would be more likely to lean into the overlapping partnerships they are building with their other neighbors, such as India, Australia and Japan — investments made to give themselves strategic options — than to decisively take the U.S. side.

Take Vietnam: Even as relations with the United States have advanced, Vietnam has pursued deeper defense ties with India, formalizing cooperation on military logistics and weapons development and moving toward arms purchases from New Delhi. Vietnam also continues to preserve high-level defense and government ties with China — a necessity given their shared border and contentious history. When Biden upgrades relations with Vietnam, it will not represent Hanoi’s picking Washington over Beijing, although many will frame the move this way.

The region has moved beyond security blocs and binary choices. The United States needs to do the same. The best way to do this would be through robust economic engagement, for example by joining — rejoining really — the now-rebranded Trans-Pacific Partnership free-trade deal President Obama negotiated and President Trump scuttled. Unfortunately, U.S. economic nationalism probably precludes this option.

Alternatively, the United States could formalize its participation in ASEAN’s subregional political and economic groups with investments of capital, materiel and technical expertise. Washington could also leverage its comparative advantages in green technology, industrial know-how or education to create new ASEAN subgroups, as it did with the five-nation U.S.-Mekong Partnership established in 2020 to promote stability and sustainable development with initiatives focused on energy, water and health security.

Above all, Washington needs to stop expecting countries to choose sides in its balancing act with China, or risk being shut out of Southeast Asia.

Kelly A. Grieco is a senior fellow with the Reimagining US Grand Strategy Program at the Stimson Center, an adjunct associate professor of security studies at Georgetown University and a nonresident fellow at the Brute Krulak Center of Marine Corps University. Jennifer Kavanagh is a senior fellow with the American Statecraft Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and an adjunct professor of security studies at Georgetown University.