[ad_1]

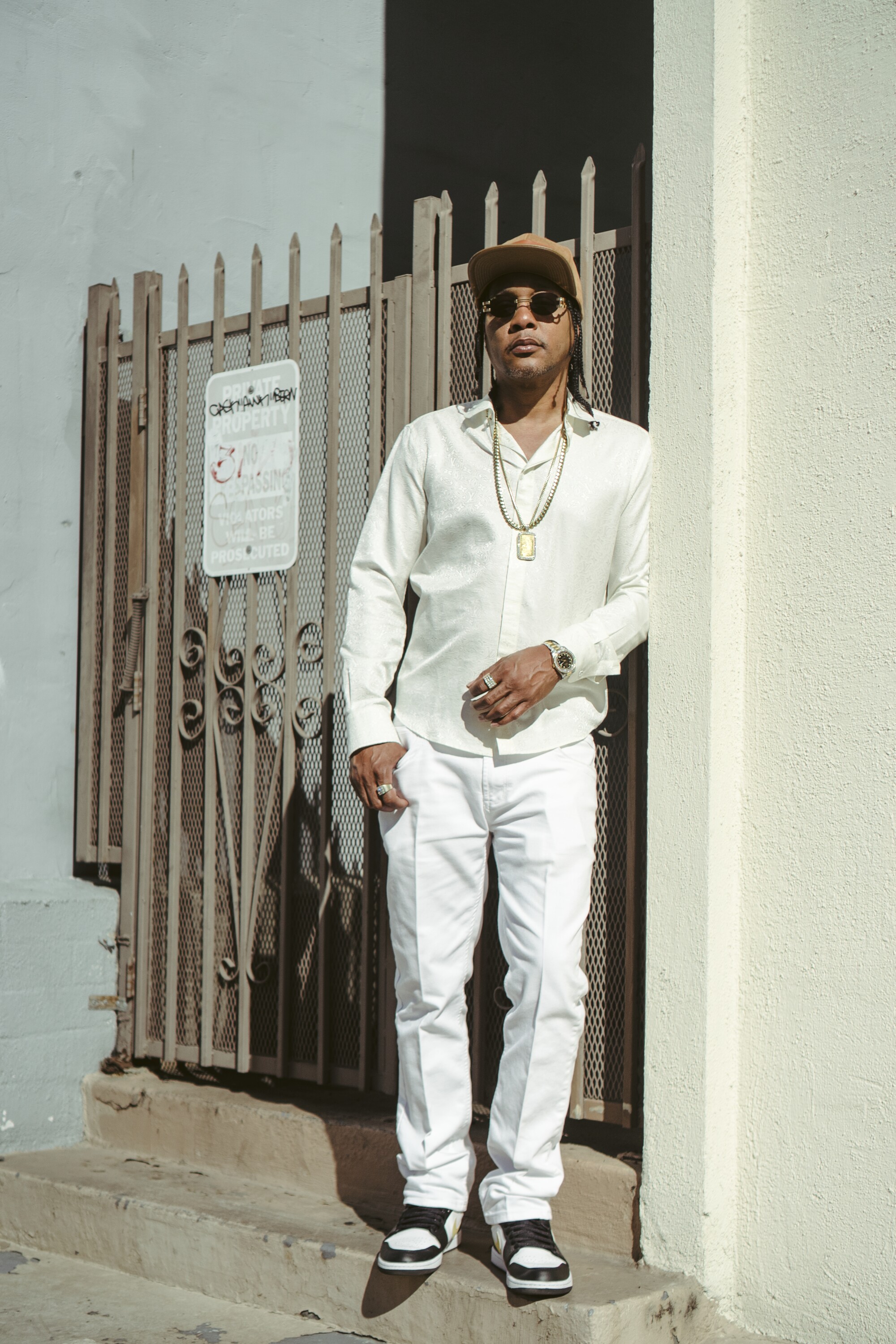

(Abdi Ibrahim / For The Times)

DJ Quik is exactly where he’s supposed to be. On an unseasonably hot Thursday afternoon in February, a blunt dangling in one hand and a perpetually half-empty cup of Champagne in the other, the permed prince of Compton — who put his home turf on the map with the release of 1991’s platinum-selling debut, “Quik Is the Name” — is holding court on a penthouse rooftop overlooking Beverly Boulevard. For the uninitiated, this is what’s known as a classic Quik groove: one that finds the veteran rapper-producer surrounded by — but, more importantly, lifted up by — friends, peers and associates. Pimp-fresh in a pair of navy blue gators is his longtime collaborator Suga Free. Others amble about, taking in a view of the city that seems to go on forever. Everyone is at ease, high on the euphoria of the moment. Quik wouldn’t want it any other way. Especially today — his mother’s birthday. Though his mother, Delma Armstrong, passed away in 2016, Quik makes a point to celebrate her every year just as she would want: with a party.

Now 52, the artist born David Blake has found the kind of clarity that comes with surviving this long in a game not set up for survival. He refers to this new life chapter as destiny. He’s finally in control of it, he tells me, keenly aware of how far he’s come and what it took to get here. “The reality is, breathing is a flex,” he says. After a turbulent career that spans more than three decades, Quik is, for the first time in a long time, clear-headed about the future and all that it has in store for him.

From the very beginning, the Compton quasar supplied L.A. with a distinct musical DNA. On songs like “Tonite” and “Dollaz + Sense,” he crafted an extraordinary geometry of sound — outfitting each track with propulsive, lowrider-chic beats, flourishes of funk, the occasional jazz influence and the kind of physically cinematic storytelling you only come across in the barbershop. His hood parables have defined eras and attitudes. His made-for-mythologizing catalog boasts nine solo albums, two joint projects — his most recent, 2017’s “Rosecrans” with Problem, is a late-career masterpiece — multiple awards and a jealousy-inducing list of production and engineering credits that includes Snoop Dogg, 2Pac, Whitney Houston, Tony! Toni! Tone!, 8Ball & MJG, 50 Cent and Jay-Z.

Recently, Quik spent time in the studio with Mustard and Vince Staples for upcoming projects. At some point, he says, he plans to release new music — and possibly an album, which he already has a title for, “David vs. Goliath” — but for now, he is content in this new period of his life, which is all about taking a back seat to produce for other artists. “I’m in the studio every damn day.”

Now 52, the artist born David Blake has found the kind of clarity that comes with surviving this long in a game not set up for survival. “The reality is, breathing is a flex,” he says.

(Abdi Ibrahim / For The Times)

It seems fitting. Or fated. Maybe it is destiny, after all. Quik has, to my ears, always operated like an orchestrator more than anything, akin to Quincy Jones or Duke Ellington. He is the kind of genius who influences generations, the kind who doesn’t simply make history but propels it forward. Because after more than a lifetime’s worth of accolades, what lasts, what ultimately refuses to fade, is a sound that Quik has made entirely his own. He is the architect of a specific, and deeply proud, local sensibility. His is the groove that never ends. The timeless house party anthem. Thirty years on, the wizard of perennial West Coast funk has remained at the center of it all. Don’t get it twisted. Quik is still the name.

Jason Parham: Where do you start when producing a song?

DJ Quik: Where does the Bible begin? I’m not trying to be smart and weird — I start at the beginning. Roger Troutman used to start in the middle or at the end and work his way back. And it was a work of art. It’s however you want to do it. If it makes sense to you, see it through. Complete the project. That’s all it’s about. There are a lot of geniuses out here that don’t finish songs. They got songs just waiting in a vault. Finishing takes a lot of commitment. See it through.

JP: You came out the gate swinging in 1991. The legend goes that “Quik Is the Name” was recorded in two weeks.

DJQ: It was a perfect jump shot. It won the f—ing Finals. It was a game seven jump shot thrown from three-point land. Who goes platinum on their debut? The people at Profile Records believed in me. Cory Robbins — he loved me. They let me live my dream out. They let me take my Compton story and put it on a song. Me and Suga Free have been doing this forever. I wanted to give that feeling to niggas I really love. I wanted to give him platinum. That’s why he did “Street Gospel” [Free’s 1997 debut], but it didn’t get marketed and promoted by Island because they didn’t know what to make of it. It was too “pimpy.” We had to go to Oakland.

JP: And they loved it there.

DJQ: They love it here. They love it everywhere.

After more than a lifetime’s worth of accolades, what lasts, what ultimately refuses to fade, is a sound that Quik has made entirely his own. “There are a lot of geniuses out here that don’t finish songs,” he says. “Finishing takes a lot of commitment. See it through.”

(Abdi Ibrahim / For The Times)

JP: Free is one of your longtime collaborators. When did that bond form?

DJQ: Tony Lane was helping me not get bullied at Death Row [Records]. He said, “I got this artist — tell me what you think.” So I go up to the shop to meet him. We slap hands. Tony was sitting behind a big desk — the Dick Griffey desk at Solar Records. Back then, Tony had a Michael Jordan baseball card that was worth $400,000. He was an investor. A card dealer. He gambled on Royal Rock. [Starts rapping like Suga Free.] I say, “Let’s get in the studio now.” And then he said, “My name ain’t Royal Rock; I changed it to Suga Free.”

JP: One of your most beloved songs together is “Do I Love Her?” How did it materialize?

Suga Free: I look forward to making Quik laugh in the studio. I thought, You know, I’m rhyming “cat” with “hat” pretty good. But once I got in there with Quik, he said “Free, keep doing what you’re doing.” He was just laughing. My pocket is that relationship thing — I find a lot of humor there. There’s a lot that goes down, coming from a pimp’s perspective. Having women come home telling me stories about what some of these tricks be wantin’. You’d be surprised what your average guy wants. Because Quik is highly intelligent, so if I can make him laugh …

Suga Free, right, is one of DJ Quik’s longtime collaborators. Both are adept at balancing realism and humor. “I look forward to making Quik laugh in the studio,” Free says.

(Abdi Ibrahim / For The Times)

DJQ: You always do, bro. It’s the look. It’s the audacity and the look. I know you too well. We Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. We really made hit records that people bought, danced to and lived by.

JP: Both of you are adept at balancing between realism and humor, which is very hard to pull off. Do you study comedians at all?

SF: Before I met [Quik], I was up on his music and noticed that he would blend Richard Pryor in on some of his songs. So I knew he liked Pryor. Once I got to know him — he could talk just like him, knew all his records. He was like me when I was sneaking up listening to my daddy’s Richard Pryor records.

JP: Quik, people have always said you have a high musical IQ.

DJQ: Is that OK? People tell me my records catch up to them six months later. But I can’t dumb this s— down. Like, give me a drug to make me stupid. I get mine from the sun. From God. From the ether. I get mine from creativity, which is a bandwidth in between reality, heaven, dreams, hell — all of that. Creativity is what you stay alive for. That’s where I’m at. I’m in creativity. I’m not unblemished by what’s going on on Earth, and I’m not trying to get all hella deep. I’m just saying where I am spiritually, why I’m happy, is because now I have a grasp on my destiny. I can’t be beat right now.

JP: When did that shift happen?

DJQ: It happened in 2016, right before my mom passed away. I lost everybody that year. I lost Prince, my mother-in-law and my mom at the same time. Delma Armstrong was an amazing woman. Today is my mom’s birthday, so I’m getting hella faded to get back in their “Soul Train,” “American Bandstand” world of hot curlers and Buick Rivieras. All that fly-ass, rich-ass s— they was doing. It’s Momma Day!

Where I am spiritually, why I’m happy, is because now I have a grasp on my destiny. I can’t be beat right now.

DJ Quik

JP: What was she like as a mom?

DJQ: The most amazing person ever. She was beyond words because she was beauty. She was like “Keep on Trying” from the Impressions. These were the records she used to listen to. Wes Montgomery’s “Bumpin’ on Sunset.” I’m like, “Damn, Momma, you playing records called ‘Bumpin’ on Sunset’ from Verve Records?” My moms was a tastemaker. She gave me the line, “If you stay ready, you ain’t gotta get ready.” [Directs his attention to Free.] Remember that day? We were working on “Street Gospel,” and my mom came to stay with me for a few weeks.

SF: Delma was very to the point and direct. One day she told Quik’s nephew, “Boy, you look like somebody dug you up, drugged you up, stood you up and f—ed you up.” My eyes got as big as paper plates. Had me crying laughing. And I got my pen and I wrote it down. And that line became a part of “I’d Rather Give You My Bitch.” I got it from her. She’s walking up the stairs and didn’t even look at him as she was talking. Delma really had an impact on the way that record sounded because there was a mother around, you know what I mean? That mom thing was …

DJQ: Heavy. My mom was so gangster. She made Suge and them leave when they tried to get me to come with them to the Tyson fight that night [On Sept. 7, 1996, in Las Vegas, 2Pac was fatally shot; Knight was in the driver seat.] She said, “If y’all don’t get away from my motherf—n’ door I’m gonna start blastin’. I’mma call the police first then shoot y’all in y’all motherf—n’ ass.” She had all the guns.

JP: What did she make of your career?

DJQ: She knew it the whole time. She trusted me with the whole family. I’m the baby. My grown-ass sisters in here with boys, dancing around playing music, living. She was like, “Son, I’m gonna give it to you. And I ain’t gonna give it to you easy, but I’m gonna give it to you.” She trusted me. She trusted me with the keys like little Willy Wonka. I broke the glass ceiling in her world because I was left-handed. I was the only left-handed kid she had. So I saw everything different from her and all the rest of her children.

JP: That sense of family seems to be a guiding tenet in your music. The belief in fellowship. Your albums often feel like a jam session with the homies. What is it about that process of coming together?

DJ Quik’s hood parables have defined eras and attitudes. “People tell me my records catch up to them six months later,” he says. “But I can’t dumb this s— down.”

(Abdi Ibrahim / For The Times)

DJQ: I love people. I was just in the studio with Mustard. I’m so proud of him and YG. They listened to us when we were younger. And we weren’t the best role models. We drank and smoked weed. Now I take mushrooms — I micro-dose. But I’m proud of these guys: 1500 or Nothin’. Rance. Brody. Terrace Martin. Kamasi Washington. Thundercat. Kendrick, Ali and Dre. Snoop just bought Death Row.

JP: That was major.

DJQ: The old Snoop bought the young Snoop’s work. He didn’t let it keep changing hands with other people eating off of him. Now he can eat off of what we call his “stick man” — his incorporation. He incorporates Death Row, he incorporates himself. He becomes the master of his destiny for his catalog, Dr. Dre’s catalog and 2Pac’s catalog. It was the smartest thing. What better fairy-tale ending? [At the time of publishing, specifics of the deal were still being negotiated, according to a report by Billboard.]

JP: What was it like working with Snoop during that late ’90s-early ’00s golden era?

DJQ: I didn’t expect him to be that cool. He didn’t have to be nice to me. But because I came out before him, and he understands that we took a hard road coming into this, he decided to tell me the truth. I didn’t even think he knew what a Quik was. But he was like, “I had your mixtape.” Snoop said he had my mixtape! They tell me that he did his hair because of the way I was doing my hair on TV — who got that flex?

JP: You regularly collaborate across genres. In 2000, you got an opportunity to work on “Fine” with Whitney Houston. How’d that come about?

DJQ: Raphael Saadiq hooked that up. When I heard the “Sons of Soul” records, I wanted to work with him. I already loved him from “Feels Good” and “Little Walter.” But when I heard “Anniversary” and “(Lay Your Head on My) Pillow,” I’m like, I have to work with him. I was at my peak. I was doing movie scores at that point. I was on everybody’s soundtrack. When Priority, Warner Bros. and all the major labels would pay for a soundtrack, they called me because I was the hit boy. I was making fast records. I was sampling all the hot s— and putting it out. I was Diddy before Diddy.

JP: At your peak, how many albums were you producing a year?

DJQ: I was producing one album for one group three times a year. Albums. I’m a workaholic. I’ve been warned about it. They tell me I am going to end up dying. They’re like, “What’s it going to be worth?” I went to Cheyenne, Wyo. Some people saw me rehearsing and said, “Why do you still go so hard?” But it’s not hard. It’s normal. This is hip-hop. I wrote “Sweet Black P—.” My life is a virtual party from the song “Tonite.” I wrote that when I was 19 years old. I arranged that song while listening to the D.O.C.’s “No One Can Do It Better” album while trying not to bite the whole thing. “Eazy-Duz-It” was in the cassette deck. I had a CD of “Straight Outta Compton.” I had to find my own thing under my big brother, Dr. Dre. I had to give him his lane. He took gangsta rap and turned it into g-funk.

JP: And what did you turn it into?

DJQ: I turned it into rhythm-al-ism. It’s just jazzy music. It’s digestible. Some of the lyrics are a little crazy. But that was back then.

JP: Let’s get into your 1998 release, “Rhythm-al-ism.” I’m a little younger than you, and I have this specific memory where —

DJQ: A little? Nigga, your gray hairs are scared to come out.

JP: I pluck them. They started coming in last year.

DJQ: Don’t do it. Give them a lane and enjoy it. Let him be the only odd man out. It’ll slow your time down. Keep your eyes on your hair. Look, I could be like George Jefferson right now — with a receding hairline. I’m 52 years old. I’m growing beautiful hair. I could dread this s— right now. I could braid it. I could turn it into a perm.

JP: You once referred to “Rhythm-al-ism” as “the beginning signs of music that I could call my own.” What did you mean by that?

DJQ: I love Prince. I was copying Prince Rogers Nelson. I f—ed with the Time and Jamie Starr. Do you know who Jamie Starr is? That was Prince when he was producing the Time because he didn’t want to have a conflict of interest within his own company. Jamie Starr and the Starr Company — Prince made that and made that his stick man. He produced the Time, bought their name and gave them a career. Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis [who are former members of the Time] left to produce for Clarence Avant and gave us more music. That’s the doubling down of Minneapolis. And that’s what I’m doing — doubling down on Minneapolis.

The album [“Rhythm-al-ism”] was definitely that. I wore Versace [on the album cover]. Look, I don’t work out. MC Eiht said I had a bird chest; he was right. I’m a musician. I wanna play the piano, bro. A synthesizer. I don’t want to fight. Dig this. I’m too old to fight the power. I ain’t making no waves. I ain’t causing revolution. I ain’t feuding with no rappers. I ain’t doing too much. I like to see people win. I like to spectate. But I don’t want to be a voyeur either. I’m not looking too deeply into anything. I just observe and leave. Like a leader does. I’m embracing my leader phase. And I like my gray hairs, nigga.

DJ Quik says he has new collaborations in the works. “I like to see people win,” he says. “I’m embracing my leader phase.”

(Abdi Ibrahim / For The Times)

JP: Thirty-plus years in the game. What’s next?

DJQ: I’m taking all back seats — especially if it has a tray table, a TV and Le Parker Meridien house shoes in the back of the car. I’m producing some of the hottest artists right now. Unsigned talent. I’m finna produce the next Lata Mangeshkar and the next Whitney Houston. I’m with Larry Blackmon right now making records. Me and Dave Foreman. I’m producing people y’all haven’t even heard of. Clive Davis was my boss. What the f— else am I supposed to do?

Jason Parham is a senior writer at Wired and a regular contributor to Image.